Three kinds of teacher

By: Huss Farsani

Word Count: 4,400

Average Reading Time: 22 minutes

CONTENTS:

Three Kinds of Teacher

The Explainer

The involver

The Enabler

Types of Teacher & Stages of a Lesson

Categories Defining Methodology

Transmission of Knowledge

Emphasizing Practice

Enabling Learners

Works Cited

|

| Source: https://allthingslearning.wordpress.com/category/curriculum/ |

It is hard to put teachers and types of teaching in discrete categories;

after all, every teacher is different, and perhaps unique, in the way(s) s/he teaches and organizes learning in the classroom (not to mention how much teachers may actually share in their practices). Nevertheless, categorizing teaching styles in broad terms allows teachers to identify elements of their current teaching, and the practices they need to adopt if they intend to implement any changes. Following Adrian Underhill’s model (Scrivener, 2011, pp. 17-19), I have attempted to present guiding descriptions of three broad categories of teaching style1:

The Explainer

|

| Source: www.pinterest.com |

This is a more ‘traditional’ style of teaching where the teacher assumes the role of a lecturer: one who knows the subject matter and transfers that knowledge to an audience, a roomful of students2. Although some explainers may be very imaginative, creative and entertaining in their delivery of information, the majority can at times bore even the most motivated of students.

Do explainers plan their lessons? In a broad sense, yes. Explainers, especially the more experienced ones, have a few notes made in advance; some may have a well-organized and full-fledged body of notes, with slide presentations or other audio-visual material they carry about. In a more strict sense of the word, however, the answer is ‘no’. Explainers do not usually have ‘stages’ in the lesson; they rather see the lesson as a whole chunk that begins with their introduction and ends when they have covered all or most of the notes/materials they have brought to class. In other words, an explainer’s notes define the course the classroom teaching (and learning) is to take, whether in a single session or the whole semester/year. There essentially is no ‘timing’ specified for a particular ‘stage’, no ‘learning objectives’ defined for the lesson (the learners are meant to take as many notes as they can during class), and no particular teacher-student patterns of ‘interaction’ identified, other than the occasional clarification questions asked by those learners in possession of a longer-sustained attention span.

In an explainer’s class, learning is to happen after class, not during the teaching. Class time is reserved for the teacher: s/he needs to fill that time up with as much ‘teacher talk’ as s/he can. Students’ inquiries are best seen as peripheral, though generally considered distracting and unnecessary (they will be answered in the course of the lecture, if the students wait long enough). Student ‘interaction’ of any kind is also a distractor, and may even be expressly prohibited in the lesson. In fact, student interaction is primarily absent in both planning and execution of the lesson. This is due to the fact that the explainer does not, or perhaps cannot, go beyond self-initiated, self-regulated explanation: in other words, s/he does not have the capability (the ‘methodology’ or techniques) to put students together in pairs and/or groups in order for them to interact. Even if s/he were capable of doing that, s/he would still be unable to hand over the responsibility of teaching/learning to the students. How can learners be expected to learn from one another when their knowledge of the subject, from the point of view of the explainer, is non-existent or, at best, insufficient? Recall that one essential premise of an explainer’s teaching is the accepted fact that s/he is the knower, the transferer of knowledge s/he exclusively possesses in the classroom; students are so-called ‘blank slates’, the recipients of this knowledge. In that sense also, ‘motivation’ is a built-in aspect of the lesson, since s/he desires to convey what s/he knows and the students long to receive new knowledge and fill a gap in theirs.

Does an explainer know his/her students? Explainers usually do not know much about their students. They may not even know their names, or perhaps not much beyond a few names that have stuck. Able explainers may know a lot about their students; however, this information has no chance of being employed in the classroom since teaching, or rather ‘explanation’, addresses all students and is not geared to or modified for one or any number of particular students.

Does an explainer carry out a ‘needs analysis’ before the lesson to identify what knowledge students already possess and what sort of information they need? The answer is ‘no’. Explainers are of two types when it comes to recognizing the needs of the students:

- One group are those who believe that students are incapable of knowing what they want. For them, therefore, the pre-determined syllabus ordained for the course determines what is to be presented in the lesson. These are teachers who base their teaching on a version of the perfect plan that is pre-decided by a knowing body of experts (usually made up of other explainers!).

- The second group are the ones that base their course syllabus on their own assumptions and perception of what the students need, rather than finding out what the students actually need. Even if there were a few students with particular individual needs, the teacher would still base the plan on his idea of the needs of the majority, and would expect those few students to comply with the needs of the ‘whole class’. Course syllabi for less experienced teachers are usually designed based on an understanding, or in some cases exact copies, of those of more experienced teachers.

Do explainers assess whether students have learned the subject matter of the course? Of course they do. This usually comes in the form of ‘summative assessment’ (Brown, 2004, p. 6) administered halfway through and/or by the end of the course. More experienced and adept explainers may also include ‘quizzes’ at various points in the course, the purpose of which is usually to encourage students to review their notes a few more times during the course of instruction. Nevertheless, the results from the assessment do not necessarily change the course of the lessons or the pre-determined syllabus in any major way. In other words, assessment does not inform the future course of action. Only some remedial teaching, in the form of repeating the same explanations one more time (by the teacher or a teaching assistant), may take place. The ‘feedback’ that students receive is either simply in the form of scores on test papers or, in rare cases, corrections made to student answers, or answers provided to the test questions by the teacher.

Several major questions remain when considering the practices of an explainer:

- How can we ensure whether the students have, in practical terms, reached the aims of the lesson, especially when it comes to second/foreign language teaching?

- How and in what contexts are the students supposed to practice and consolidate the knowledge they have received from the teacher within the realm of the four language skills (speaking, listening, reading, and writing)?

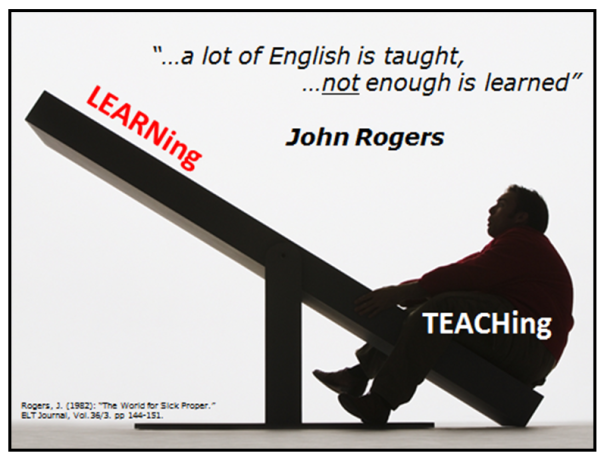

One should bear in mind that teaching does not mean the ‘teacher talking all the time’ or the ‘teacher teaching all the time’. Teacher teaching and talking do not necessarily, or may not at all, lead to any true learning on the part of the learners.

The Involver

|

| Source: http://images.wisegeek.com/college-classroom.jpg |

Perhaps the major difference between an explainer and an involver, as mentioned by Scrivener (2011, p. 18), is that the latter has ‘knowledge of methodology’ besides having a good command of the subject matter. Methodological knowledge comes in two forms, namely a) knowledge of teaching strategies, and b) knowledge of how effective learning takes place (plus a range of learning activities to be made use of in the classroom). As such, an involver’s typical lesson consists of a sequence of activities organized for the learners, and the teaching strategies essential to set up and run those activities. In addition, the involver may use a variety of techniques, tools, and activities, such as drama, student projects, and games to engage the learners in the process of learning.

Can an involver engage ‘all’ the learners in the lesson? By designing, or bringing to class, truly genuine and interesting activities, the involver is probably able to attract the attention of many more learners, and perhaps engage them cognitively and affectively in the task. However, still some learners may not be able to take full advantage of the activity introduced since the ‘level of involvement’ is something decided by the learner and the extent to which s/he is ready and willing to contribute to the task. If the task proves uninspiring or does not succeed in attracting the attention of as many learners as possible, then it may not deliver the exact same outcome for all the learners.

Can an involver help the class successfully reach the goals of learning? The answer to this question is probably ‘no’! Perhaps the biggest difference between an involver and an enabler (see Table 1 below for comparisons) is that the former can engage the learners without really succeeding in satisfying the objectives of the lesson. In other words, an involver may ‘involve’ the learners in actual tasks, but may not have devised the necessary steps and ingredients that would otherwise help learners turn ‘input’ into ‘intake’ (for a discussion, see Schmidt, 2001).

In my own experience of various language teachers, I tend to think of an involver as a fun and smart teacher. They can also be very inspiring and engaging in the way they deliver the lesson. Some of these teachers are probably ones whom I would label ‘explainer-turned-involver’: they are the ones who were smart enough to realize lecturing does not necessarily lead to active learning, and then tried various methodologies or adopted certain classroom techniques that would allow them to involve learners in the process. In other words, they gave learners a share of the classroom practices that would let them carry out part of the teaching/learning on their own.

As fun as an involver may be, they rarely become enablers, for several reasons:

- Explanations, sometimes quite lengthy but nonetheless fun, still have a place in this kind of teacher’s lessons. Their ‘conversion’ from an explainers’ paradigm may have instilled the general idea of ‘first teach then practice’ in their overall view of learning and teaching.

- Engagement and fun may be important features of an activity that involves learners. However, knowing the ‘aims’ of each activity or a related sequence of activities will enable learners to work toward a particular goal in developing their proficiency. Involvers often neglect, or do not succeed in, communicating the aims of an activity, a stage, a lesson, or even those of the whole course to their learners. For the same reason, they often also fail to take feedback on learners’ perception and mastery of the objectives of the lesson.

- Most importantly, and perhaps in the same vein as explainers, involvers often also base their presentation of (sequences of) activities on their intuitive understanding of learners’ needs. This is closely related to 2 above, and to the inability to ‘build on’ learner feedback to modify activities in the course of a lesson. Of course, many such teachers have strong intuitions about learners’ needs and preferences. They may even build in the lesson activities that help with learners’ errors in various aspects of the systems (grammar, lexis, and pronunciation). Enabling learners, however, goes beyond a sole treatment of errors.

Involvers often become frustrated over why their learners do not seem to be improving over the course of the semester; they seem to engage in a lot of activities, but the outcome is not apparent in the way learners move forward in the lesson. This certainly has a lot to do with initial needs analysis, distinguishing between practice and production, as well as taking feedback relevant to the aims of the lesson: three of the major criteria that differentiate involvers from enablers.

The Enabler

|

| Source: https://anglistik.uni-graz.at/en/fachdidaktik/neuigkeiten/detail/article/photos-from-workshop-on-learner-autonomy/ |

The enabling teacher is one who a) knows the subject matter, b) knows methodology, and c) knows the people s/he teaches, their physical, cognitive, and affective needs. S/he may apply his/her knowledge of ‘multiple intelligences’ to the learners and their styles of learning. The enabler, in this sense, does not teach the whole class: s/he is actually micro-teaching individual learners, or groups of learners, according to their particular styles and needs.

The enabler has a lesson plan that goes beyond just teaching the subject matter and ‘involving’ learners: s/he actually is able to hand over the responsibility and task of learning over to the students. In fact, the enabling teacher’s roles change depending on the stage, the activity, and the requirements of the task. However, their lessons do not just comprise a series of activities to be completed by the learners; the sequence is designed, punctuated with feedback loops that inform the next step, so as to increase the enabling factor: aiding learners in reaching the aims and objectives of the task/lesson/course of instruction. The carefully designed lesson plan is usually based on a rigorous ‘needs analysis’ procedure carried out by the teacher shortly before or at the start of the course. Moreover, the plan for each lesson specifies and anticipates the possible problems of learning that might happen in the course of learning/teaching, and concrete solutions to tackle them.

The major question here is: what is it that distinguishes an enabler from an involver?

Here are 10 features that distinguish enablers:

- They recognize the ‘communicative’ value/purpose of a task3 and build language systems/skills practice around the learners and their communicative needs; they promote all aspects of ‘communicative competence’ and not just ‘linguistic competence’ or simply knowledge of language (see Canale & Swain, 1980, for an original discussion of the term communicative competence);

- They enable communicative interaction, not (just) between the teacher and learners, but between learners themselves so as to increase ‘student talking time’ (STT) and to allow learner response to and control of the task;

- ‘Challenge and change’ is their motto in designing tasks. They initially challenge learners to receive feedback on both what they are capable and incapable of doing. They then build on learners’ capabilities to introduce new activities that gradually involve learners and guide them in dealing with new language/skills they initially were incapable of processing. Task difficulty will increase until learners are able and confident to apply what they have learned to a challenging ‘real-life’ situation;

- They break ‘complex tasks’ (ones that may involve multiple skills) down into manageable chunks that help learners perform well, receive feedback, and gradually move toward the end goal.

- In order to increase learner control and contribution in carrying out learning activities, they include ‘learner training’ in their classroom activities; in other words, they also include ‘study skills’ and ‘learning how to learn’ techniques as part of their classroom practices in order to increase ‘learner autonomy’;

- They share the aims of the lesson with the learners and increase awareness toward achieving a practical learning goal (e.g. making a presentation in the real world or passing a skill-based exam at school); they also consider and convey to the learners the future contexts of use of what they (are supposed to) learn in class. They constantly ask themselves ‘What exactly [do I] want [my] students to be able to do when the lesson is over?’ (Lemov, 2010, pp. 9-10) and clearly communicate this to their learners.

- The activities do not just include knowledge of the subject matter, i.e. the systems of language (language knowledge), but also ways to develop the four skills (language ability), i.e. (listening, speaking, reading, and writing);

- Their activities include language ‘notions’, i.e. the ideas to be conveyed (e.g. time, space, etc.) as well as ‘functions’, what the learners need to be able to do using the language they have learned (e.g. how to apologize or how to end a formal speech) ;

- They emphasize ‘process’ over ‘product’: the lesson may contain few or no quizzes or final examinations but it surely contains ‘checkpoints’ in the form of stage and lesson feedback time (this can be formal or informal, spoken or written, whole-class or individual), where learners demonstrate and reflect on the language they have learned or the abilities they have acquired/enhanced during the lesson; this, in turn, informs the steps the teacher will take in subsequent stages and lessons.

- Motivation for enablers is subtle: it lies in the way they design or adapt tasks for their learners. Since they are fully aware of their learners' needs and preferences, they adopt tasks that correspond to those particular needs and preferences.

Perhaps the hallmark of an enabling teacher is his/her ability to not interfere in the process of learning other than to guide, help, counsel, and support, i.e. to create an environment that is conducive to learning and not to teaching. These teachers are often the ones that create enthusiasm that lasts beyond their classes, take-away values from their lessons that have a lifelong impact on the learner & his/her linguistic ability.

Types of Teacher & Stages of a lesson

A look at various stages of a typical lesson will show how different kinds of teachers plan, emphasize, and execute their lessons:

|

| *No - **Maybe - ***Yes (Note: You can click & copy this table for your own use) |

It is rather unfortunate that an involver can get so close to enabling learners but misses out on key activities that would otherwise help learners reach that point. I know this from personal experience: prior to doing DELTA Module 2 (Developing Professional Practice), I lagged behind as an involver. I was a funny teacher, my students loved my classes, and the contents/activities that I chose for the lessons were super-engaging. However, at the end of the day, I could clearly see that my learners could not go beyond what they had been given in the lesson4, and even worse, did not exhibit the language proficiency that I expected of them, and they expected of themselves after so much effort, at the end of the semester.

Categories defining methodology

As I mentioned earlier, knowledge of methodology is an important ingredient that differentiates between styles of teaching. However, a close look at the history of ELT methodology will demonstrate how methods themselves can be differentiated in terms of transmitting knowledge, emphasizing practice, and enabling learners.

Transmission of knowledge

Perhaps the best-known case in this respect would be the traditional Grammar Translation Method (early 20th century). It was a method characterized by an emphasis on knowledge of grammar and vocabulary meaning along with the skill of reading – and translation (of written material). Its neglect of the many practical skills and components involved in learning/using a second/foreign language led not only to inability in the ‘use’ of what was learned, but also reactions from the language teaching/learning community that eventually led to the emergence of other methods.

Emphasizing practice

The Audiolingual Method of the mid-20th century, influenced by the linguistic school of structuralism and the psychology school of behaviorism, was perhaps based on the assumption that ‘practice makes perfect’ (or in precise behavioristic terms, that repetition and reinforcement make perfect). Audiolingual practitioners stopped emphasizing the transmission of knowledge and instead began to teach language (especially grammar and vocabulary meaning) inductively, allowing learners to infer knowledge through patterns of extensive practice. However, there seemed to be no reason in explicitly specifying the aims of the lesson or building on learner feedback to decide which direction the lesson would take (in fact, learner feedback, especially errors, were to be corrected immediately, before they had a chance to turn into habits and become fossilized5).

Enabling learners

Among the many innovative methodologies that were proposed in the 1970s in reaction to Audiolingualism, one in particular stands out: Community Language Learning (Curran, 1976), in which the teacher acts as counselor, helping a monolingual group of learners work together to learn a particular aspect of language or to develop a situational conversation. Probably this was the closest a method could come to the actual needs of the learners, enabling them in the course of classroom interaction to reach learner-defined aims. A major shortcoming, however, was that the process of back-and-forth translation between learners and the teacher-counselor resulted in undue emphasis on language (and translation) rather than the ‘task’ which was to take center stage.

The Communicative Language Learning of the late 20th century was an approach that began looking, both in terms of theory and practice, at the knowledge of language as well as skills as used in real-world communication (Canale & Swain, 1980). The fact that researchers and practitioners began looking at the various linguistic and extra-linguistic factors that enabled proficient speakers to ‘communicate’ in a typical real-world situation allowed them to look at the ‘end goal’ of language/teaching learning, and therefore, to base classroom efforts on building toward this ‘ability’. Thus, perhaps for the first time, teachers, textbook writers, and learners were obliged to look at the end goal and adjust materials and practices according to those specified aims.

Task-Based Learning (Willis & Willis, 2007) took this at least one step further: it brought the actual real-world ‘tasks’ into the classroom, beginning with learner production and interaction within those real-world conditions (the motto being ‘communicate to learn language’ rather than ‘learn language to communicate’) and filling in communication gaps wherever possible to enable learners in terms of their precise linguistic/communicative needs. As a matter of fact, in Task-Based Teaching, learners are allowed to recognize their own needs and work to fulfil them within the framework of a task, with the teacher there to scaffold learning in terms of the needs and conditions that arise as a result of learners engaging in a certain task (Van Avermaet & Gysen, 2006).

Works Cited

Brown, H. D. (2004). Language Assessment: Principles and Classroom Practices. London: Pearson Longman.

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). 'Theoretical Bases of Communicative Approaches to Second Language Teaching and Testing'. Applied Linguistics 1 (1), 1-47.

Curran, C. A. (1976). Counseling-Learning in Second Languages. Illinois: Apple River Press.

Lemov, D. (2010). Teach Like a Champion. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, Wiley.

Schmidt, R. (2001). Attention. In P. Robinson (ed.), Cognition and Second Language Instruction (pp. 3-32). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Scrivener, J. (2011). Learning Teaching: The Essential Guide to English Language Teaching (3rd ed.). London: Macmillan.

Van Avermaet, P., & Gysen, S. (2006). From needs to tasks: Language learning needs in a task-based approach. In K. Van den Branden, Task-Based Language Education: From Theory to Practice (pp. 17-46). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Willis, D., & Willis, J. (2007). Doing Task-Based Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

1 The model pertains specifically to the practice of (English) language teaching. However, the categories and their description can also be applied/adapted to fit other teaching/learning environments.↩

2 I have avoided using the term ‘learner’ in this particular section mainly because the audience in such teachers’ classes is seen as the recipient of the teacher’s knowledge. Moreover, as I explain later in the text, in such classes, learning is not something that is meant to happen 'during' classroom teaching.↩

3 The term ‘task’ is used in a specific sense here. In English Language Teaching (ELT), a task is an activity that involves the learners in communicating to achieve a real-world outcome through the use of the target language (Willis & Willis, 2007, p. 12)↩

4 A common shortcoming of an involver’s lesson is the lack of clarity between where practice ends and production begins. Production, in this sense, should involve the introduction of a ‘real-world’ situation where learners put practice to use.↩

5 This also applies to the involver's 'feedback stages' in Table (1) above, where feedback takes the form of mere error-correction, and does not inform decision-making on a global level for the lesson(s) to follow (contingent upon note 4 above)↩

This is great stuff. Thank you for posting this.

ReplyDeleteGlad you found it useful

Delete